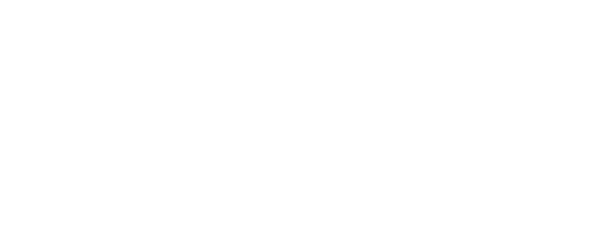

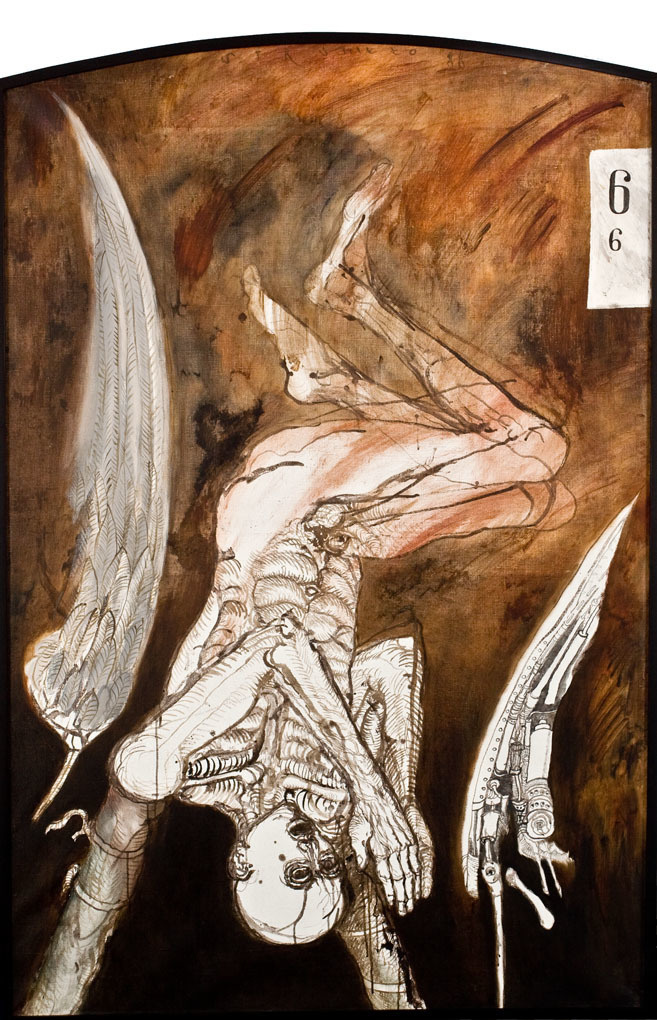

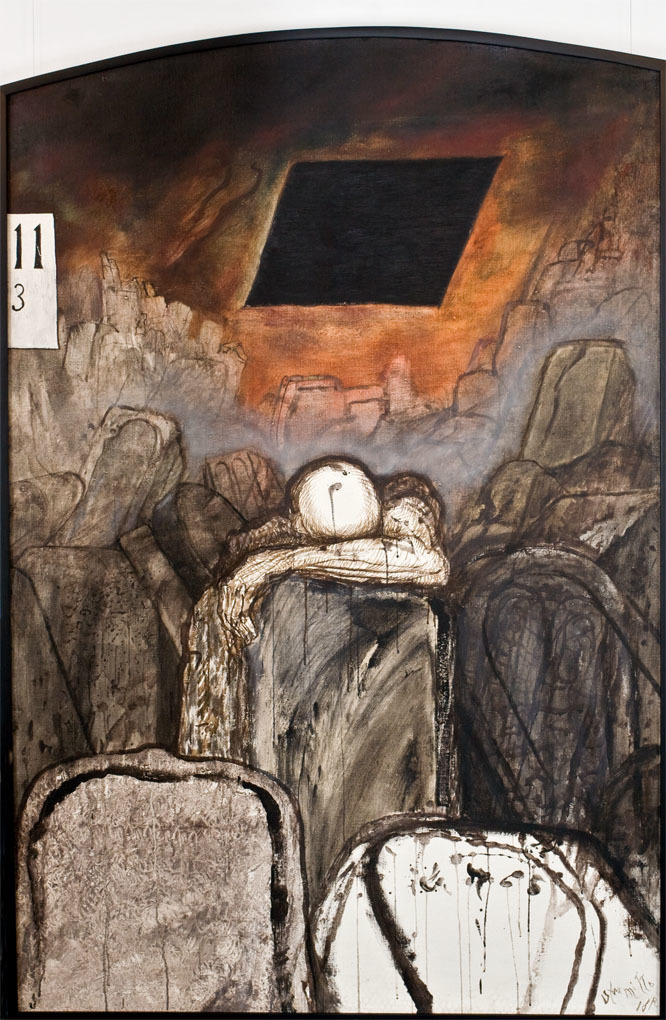

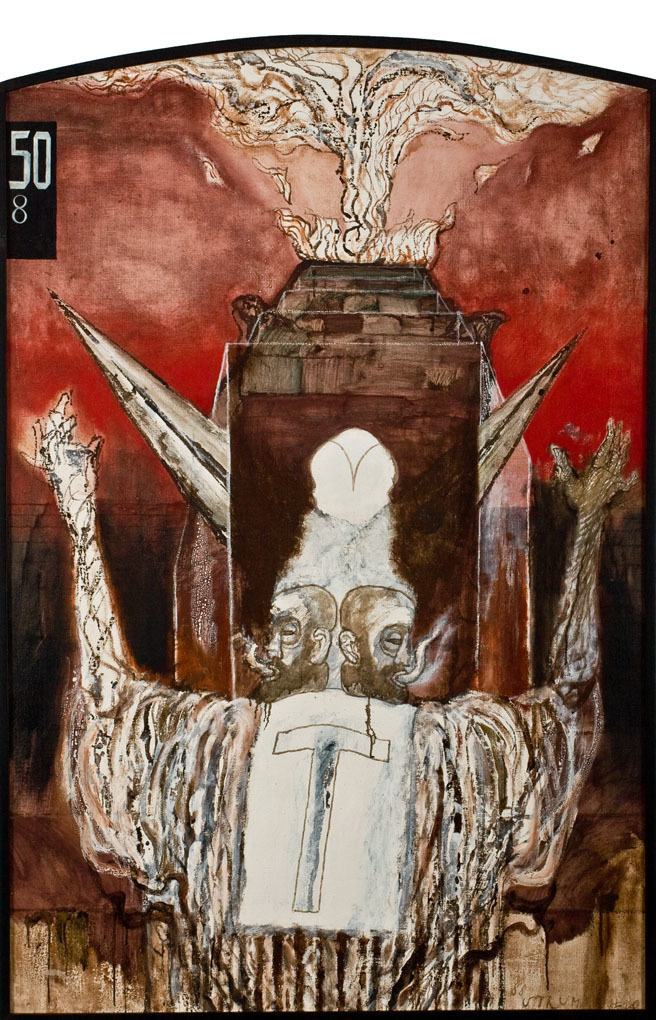

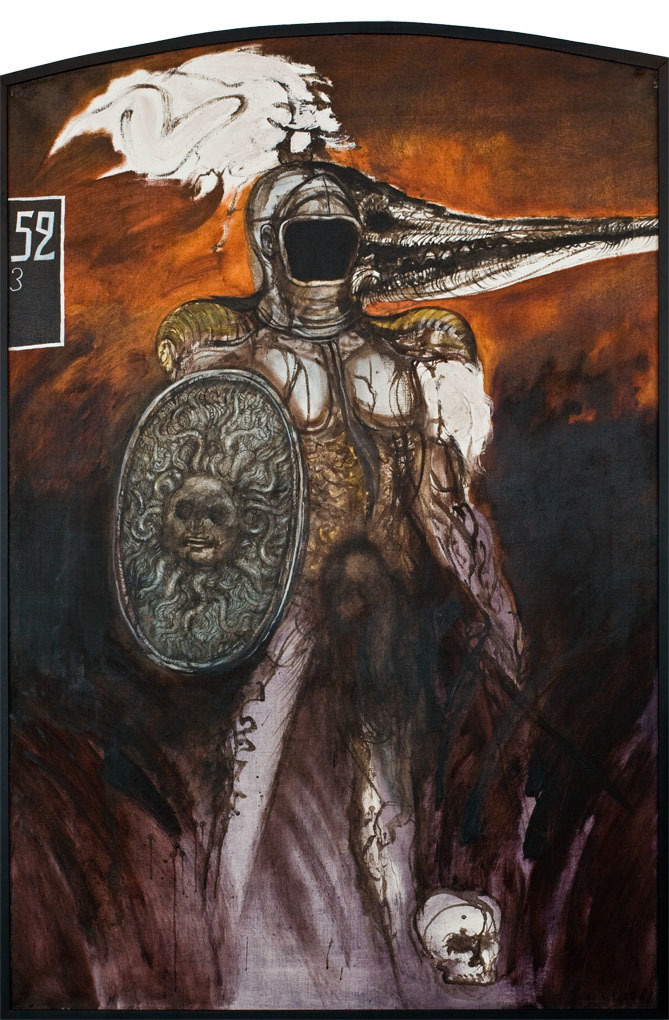

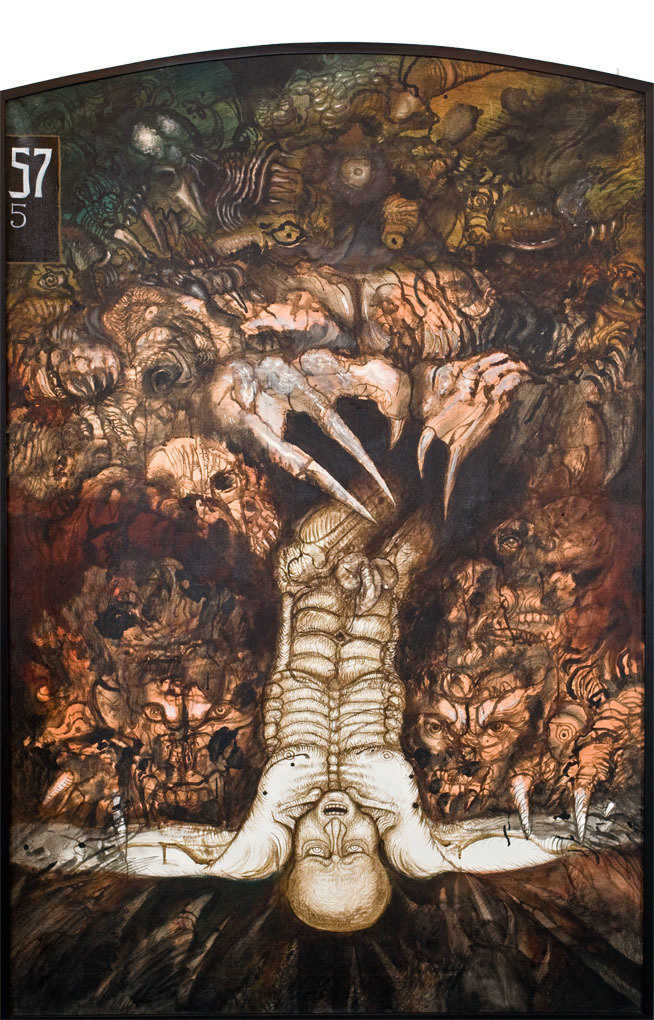

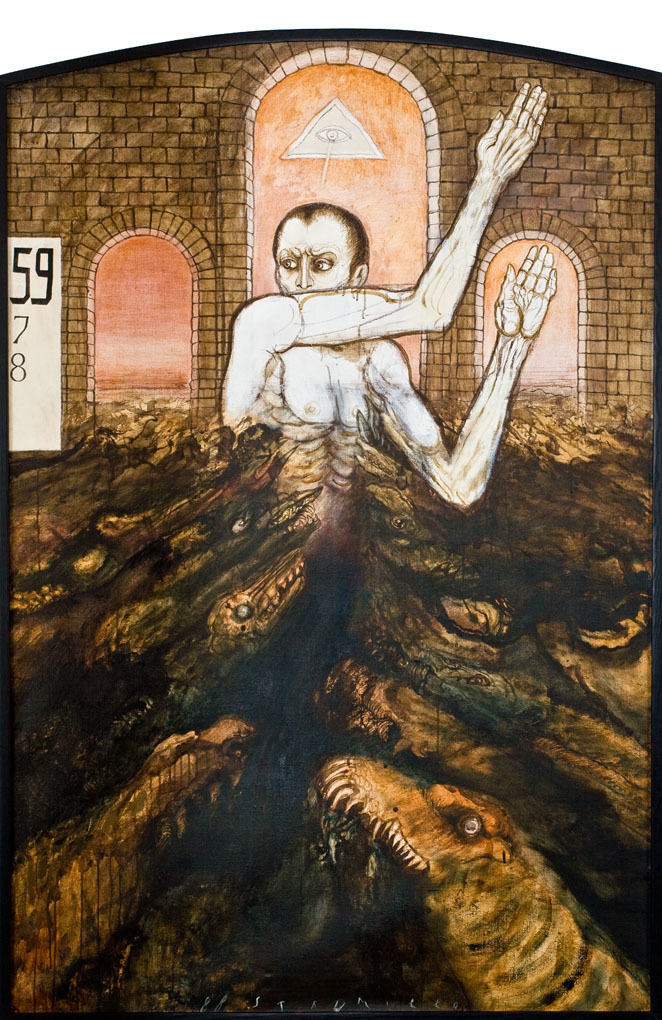

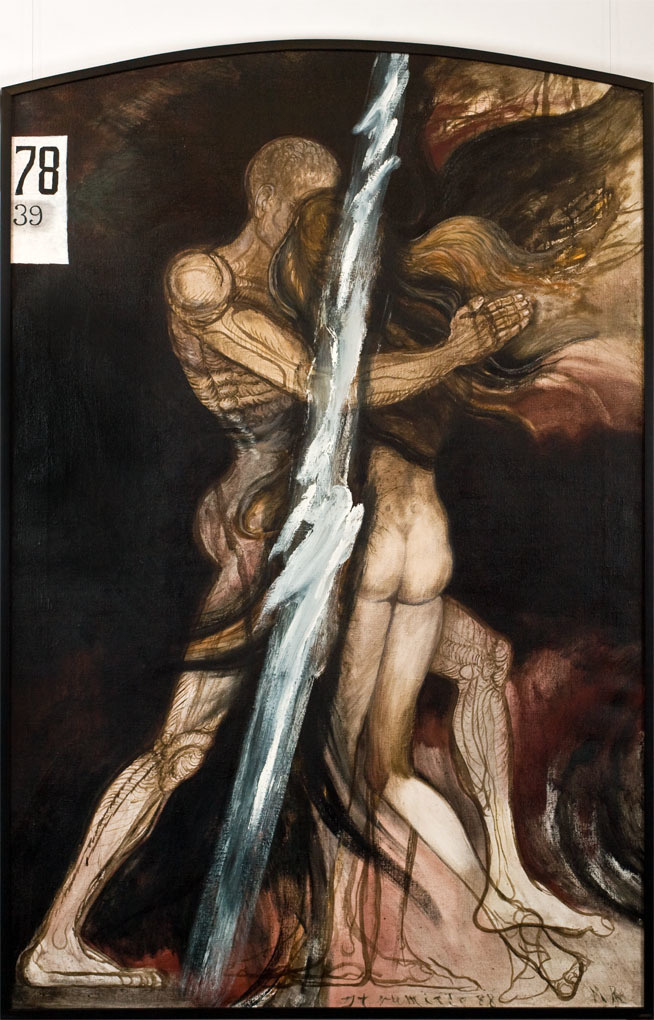

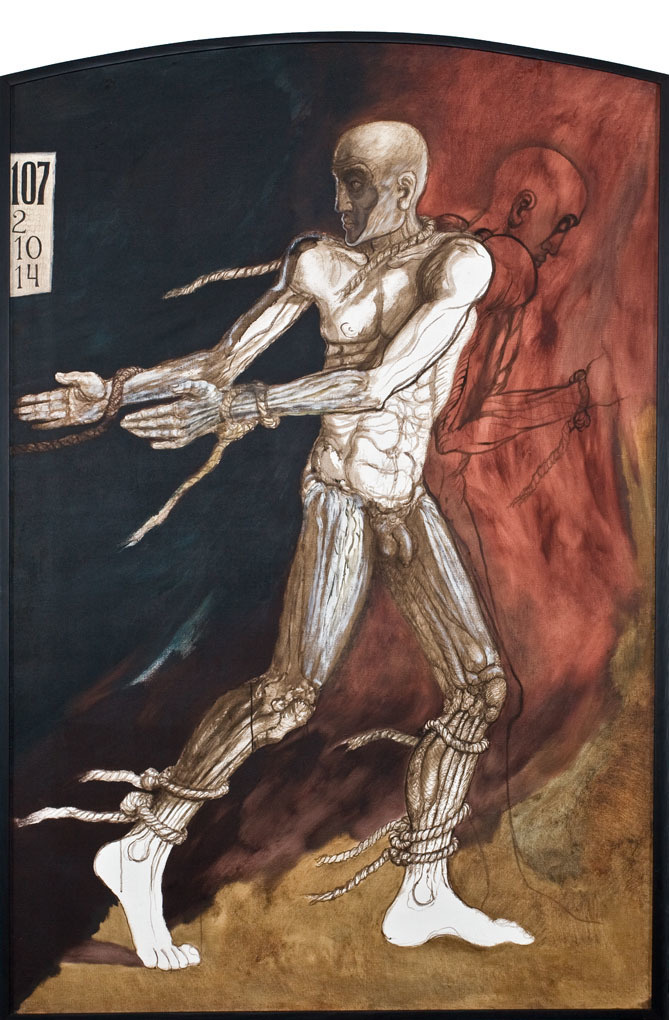

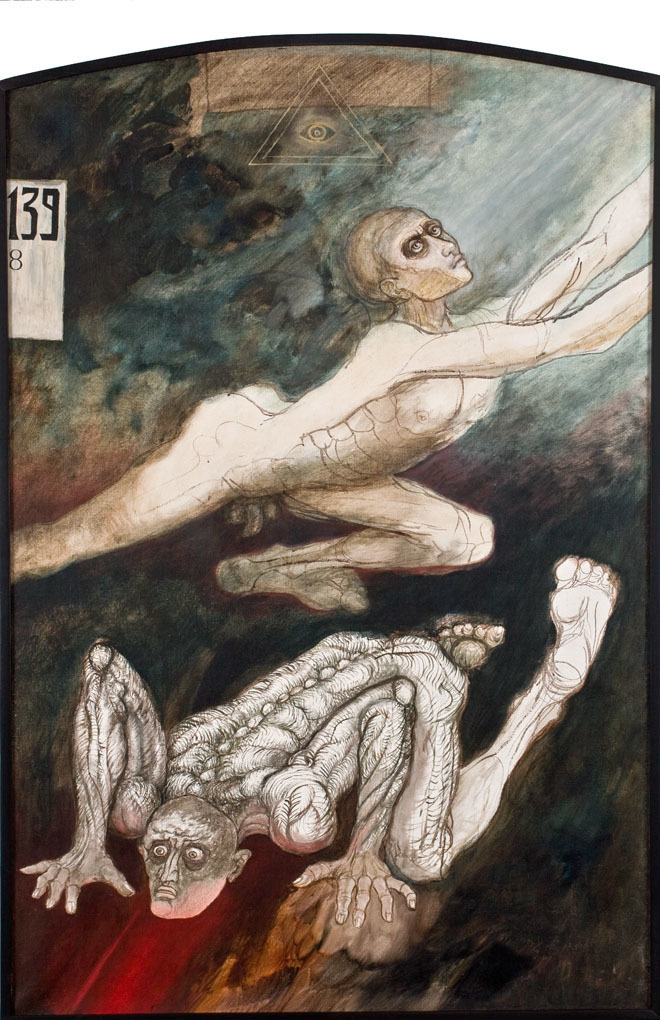

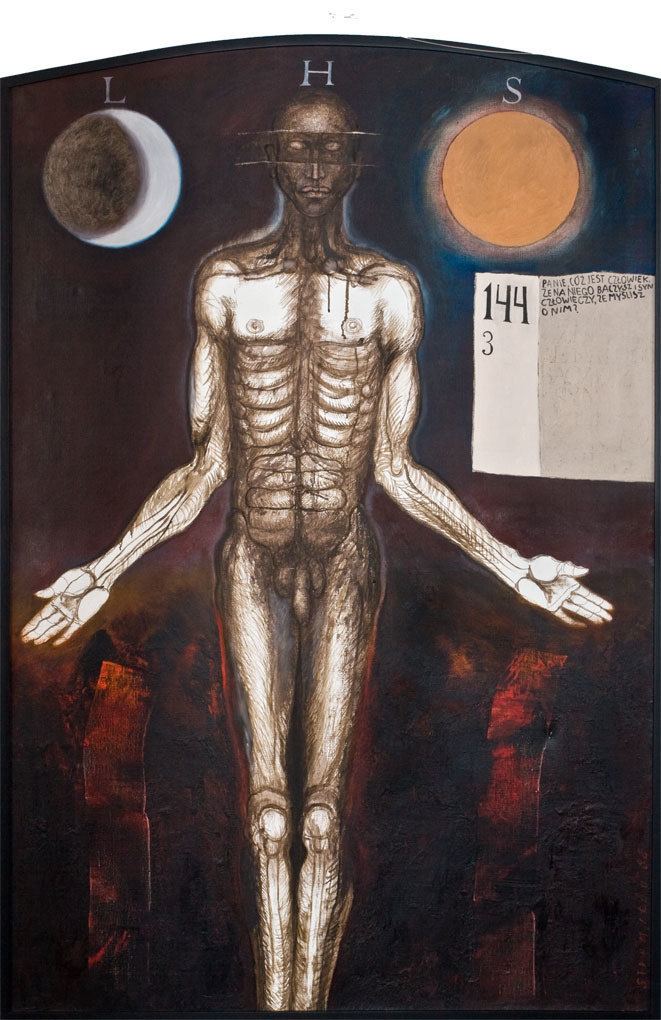

The series “Psalms” — 1988

In 1988 I painted eighteen pictures which make up the “Psalms” cycle for the rebuilt synagogue in Sejny.

I dedicated that work to the memory of Jews. In the little towns in than Polish-Lithuanian borderland there were often more of them than the Poles and Lithuanians. In the years 1860 — 1870 the Jewish community in Sejny built an impressive prayer-house in the style which was a mixture of the Classical and Neo-Gothic. During World War II it shared the fate of the community. It was a prison and a fertilizer store. Today Sejny boasts the white restored walls of the Beit Knesset.

I knew very well that the Pentateuch authoritatively forbade the Jews — and this prohibition was repeated several times — to create figurative works of art. You shall not make a carved image for yourself nor the likeness of anything in the heavens above, or on the earth below, or in the waters under the earth — that is what the God of Israel told Moses on Mount Horeb. That law forbade to paint the figures of God and man. Synagogues were decorated with painted canopies, tents, carpets cloaks and curtains, as well as folds, lambrequins and fringes. Among plants and flowers, vine shoots, dates and pomegranates, also the signs of the Zodiac, hands and symbolic animals, such as the deer, lion, tiger, eagle, leviathan, and musical instruments were painted. Holy cities and scenes from the Bible were presented in such a way that men were left out. Each wall-painting contained also letter compositions, mainly quotations from the Scripture, prayers or dedications to the founders.

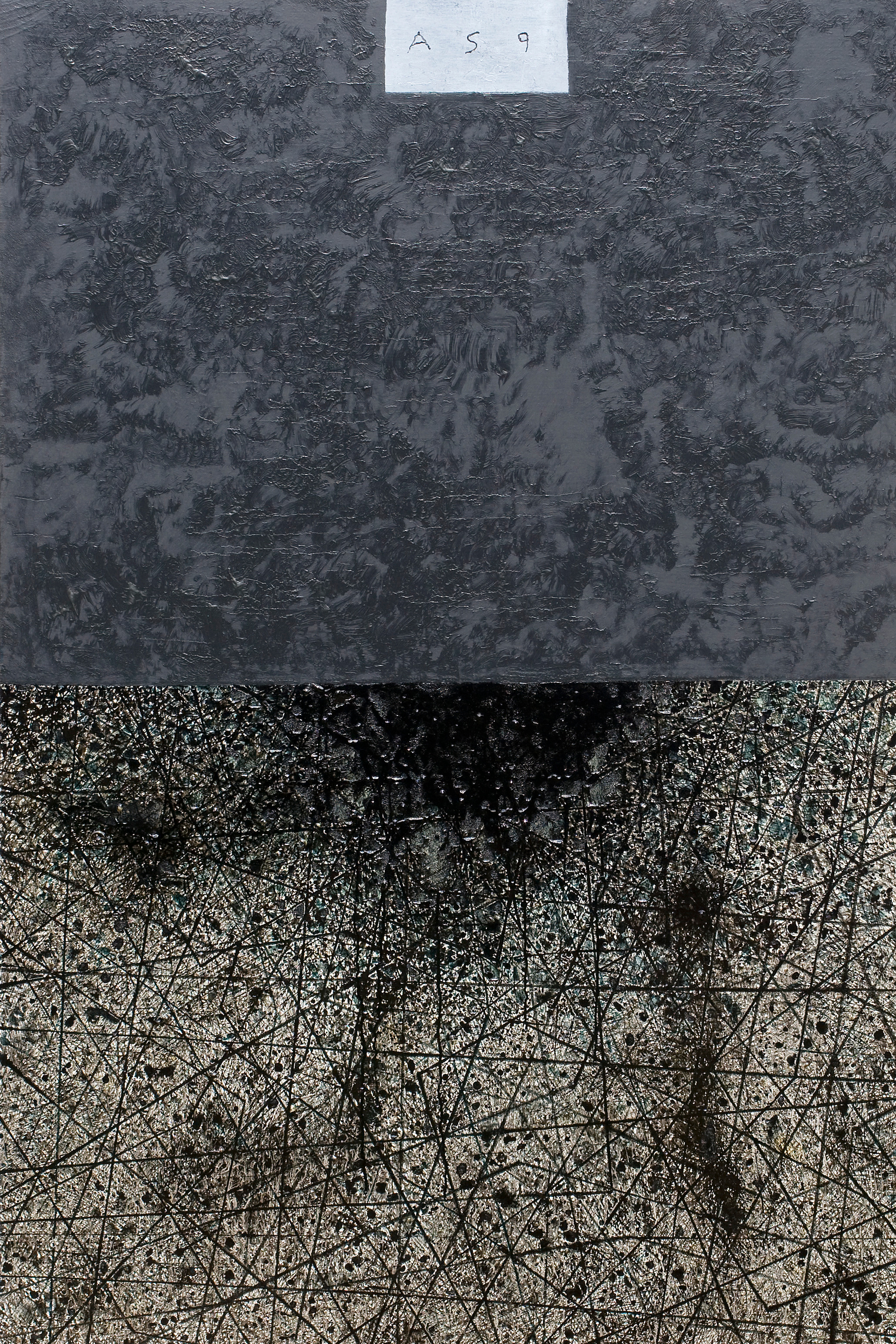

Therefore I first thought of an abstract homage. Of a black-and-grey-and- white painting. Of the painting based on restrained metaphor and suitably austere synthesis. Of the matter which would be coarse, plain, decrepit, burnt- out, downtrodden, dusty, and essentially dramatic. In my search for a language of common communication I reached for the Psalms.

The Psalms are a record of Israel identity. The Psalms, which are a sort of IP of the individual and the nation, superbly express the universal character of human reality as well. That paradox, that contradiction of the concrete and the universal, is only a seeming paradox in the Psalms, as it is the case in each great work of art. Where these two contradictory values appear, a unique, original and universal work is created. I first found inspiration and justification in these words of Father Jozef Sadzik, in his introduction to the most recent Polish translation of the Psalms from the Hebrew by Czeslaw Milosz, published by Editions du Dialogue, Paris 1979.

It might have also been the fault of my imagination which is of illustrative character, or perhaps the in influence of medieval anonymous painters. Or maybe the neighbourhood of the village of Krasnogruda, which can be reached from Sejny after an hours’s ride. I felt justified for the second time when a year later I stopped in front of the manor house at Krasnogruda, in the company of the Poet. We were both enfolded by the world of the Psalms. The poet hid his face in the shadow of the trees. I thought about the bitterness of passing away and about undeserved suffering.

It happened that at last this autumn I could present the pictures from the Sejny synagogue in the M. K. Ciurlionis Museum in Kaunas. At the opening ceremony the Psalms were recited in Hebrew, Lithuanian and Polish. The Jews from Kaunas admitted to being deeply moved. When my health was drunk with kosher wine in the blue-and-white synagogue, I felt justified for the third time.

The winter nights at the village of Mackowa Ruda are long. I read the Psalms,

selected some of them and made sketches. Finally I chose eighteen Psalms

out of a hundred and fifty. Just as the number of fields under the windows of synagogue. My selection was affected not only by the dramatic parallel to the fate of the Jews of my time, but also by the visual qualities which inspired my

imagination. I avoided mass scenes. Man is solitary here, apart from the double-

faced priest and the intertwined couple, the saved and the damned together.

Man is accompanied with his attributes and with space. That is all I can do. Man is

de ned neither by his race nor by his epoch. He stands blind and naked between

the sun and the moon, created, as well as these heavenly bodies, out of fiery

magma. The Psalmist asks: Lord, what is man, that thou takest knowledge of him

or the son of man that thou makest account of him! (Ps. 144,3) This is the nal

question of the cycle.

Andrzej Strumillo — Mackowa Ruda, autumn 1990 Psalms Apokalypse, the catalogue, BWA, Suwalki, 1993

The series “Psalms” is in the District Museum in Suwałki